Take a stroll today through the quiet Derbyshire town of Hayfield and you’ll get a sense of understated affluence.

There are no obvious grand country houses, no palatial mansions. But it has that comfortable feeling so often encountered in country towns and villages. Adding to that feel is the steady stream of expensively clad walkers setting out from the town for the high ground of the Peak, their brightly coloured Gore-Tex rustling as they check their GPSs and consult their maps.

There’s likely a line of cars parked for hundreds of yards along the Kinder Road, leading to a quarry packed with even more vehicles, all of which will have disgorged their occupants to climb to the sometimes crowded plateau of Kinder Scout, the Peak District’s highest point.

Yet how different it must have been 75 years ago, when a ragged band of scruffy millworkers, mechanics and engineers, dressed in shabby jackets and cobbled-together old work boots walked in high spirits for a trip, the consequences of which would resonate for decades.

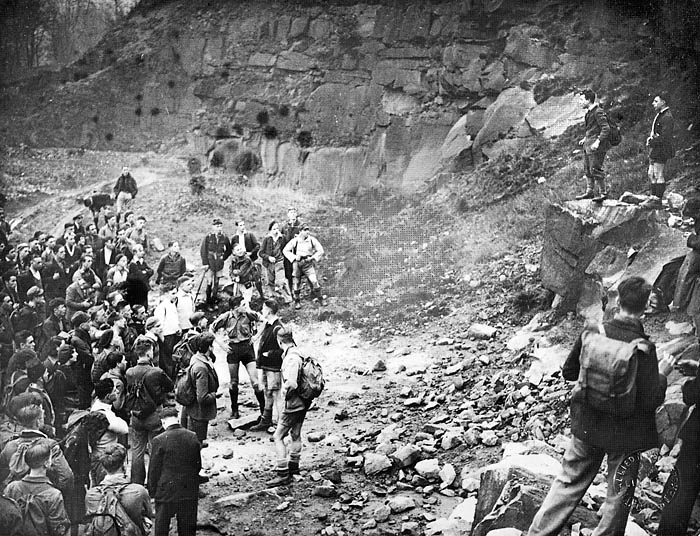

Benny Rothman addresses ramblers at Bowden Bridge quarry before the trespass

Benny Rothman addresses ramblers at Bowden Bridge quarry before the trespassUnofficial leader of the ragged- trousered wanderers was Benny Rothman, a 20-year-old Communist activist from Cheetham in Manchester, who rallied the 400 or so young, working-class walkers from the industrial heartland of Lancashire in Bowden Bridge quarry on the edge of the town before they strode out for what would be known as the Battle of Kinder Scout.

Say the word rambler nowadays and – with apologies to the massed ranks of the Ramblers’ Association – it conjures up a picture of a grey-haired, middle-class, well spoken man or woman, strolling through the countryside with flask and sandwiches, heading along the footpaths of England’s green and pleasant land for a breath of air on a summer’s afternoon. But in the 1920s and 30s, many ramblers saw themselves as part of a class army, battling to regain the open land that had been snatched from the workers 200 years previously.

The trespassers set off for Kinder

The young men and women who took part in the Kinder Scout mass trespass on 24 April 1932 were escapees from a world we can barely imagine now. Workers and labourers in the grim factories and mills of Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds, they saw the moors and fells of the Peak District as their weekend salvation: a land of greenery, fresh air, big skies and freedom.

The moors must have seemed to some of the youngsters who spent most of their lives in the bleak industrial hell-holes of the North as exotic a place as Chamonix or Zermatt, alighting in their thousands from the crowded trains that stopped at stations in the Hope Valley or New Mills on the western edge of the High Peak.

Yet there was a problem. Ever since common land was appropriated by the rich landowners of England during the 18th and 19th centuries under a succession of Enclosure Acts, the upland moors of the Peak were largely out-of-bounds, reserved for the privileged few who used them for a dozen days in the year to blast a few unfortunate grouse into oblivion.

The rest of the year they were deserted, save for a few gamekeepers, ever ready with sticks and sometimes guns to repel any oik who might deign to step on to the hallowed peat uplands.

And so had begun the rambling movement. It is true that many of the established rambling societies eschewed direct action. They came to agreements with the landed gentry to allow a day or two’s limited access to the hags and groughs of the Peak, while tugging their forelocks in gratitude. The young hotheads of Benny Rothman’s British Workers’ Sports Federation must have seemed like the ‘chavs’ of the inter-war years. The Stockport group of the Holiday Fellowship declared its utter disgust at what it called organised hooliganism. The Manchester District Ramblers’ Federation would, it stated in a telegram, take no part in the events at Kinder.

But how many modern-day urban youths could boast of reading Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists or quote passages from Upton Sinclair? The young ramblers who assembled that April 75 years ago were part of a political movement as much as a recreational organisation.

The Kinder mass trespassers had originally intended to gather in Hayfield’s recreation ground, having distributed handbills and chalked messages on the town’s roads. A few weeks earlier, a party of ramblers had been turfed off Bleaklow, to the North of Kinder. The town’s Parish Council, horrified at the prospect of this invasion of working-class hooligans, prepared to order the group to desist, its bylaws forbidding meetings on the ground. It called in the county constabulary in support.

Benny changed his plans and the group assembled in Bowden Bridge quarry, where a brass plaque now marks the event. From there, they set off up the Kinder Road, heading for William Clough, the steep-sided ravine leading up from the reservoir towards the summit plateau. Half way up the clough, they were spotted by a small group of the Duke of Devonshire’s men, some of them elevated to ‘temporary gamekeeper’ status, who were high on the upper slopes, below Sandy Heys. The trespassers, who had set off from Bowden Bridge singing The Red Flag and The Internationale, confronted the gamekeepers.

Benny changed his plans and the group assembled in Bowden Bridge quarry, where a brass plaque now marks the event. From there, they set off up the Kinder Road, heading for William Clough, the steep-sided ravine leading up from the reservoir towards the summit plateau. Half way up the clough, they were spotted by a small group of the Duke of Devonshire’s men, some of them elevated to ‘temporary gamekeeper’ status, who were high on the upper slopes, below Sandy Heys. The trespassers, who had set off from Bowden Bridge singing The Red Flag and The Internationale, confronted the gamekeepers.

National Trust sign at the bottom of William Clough: right to roam

A Manchester Guardian report from 25 April 1932 says: “There followed a very brief parley, after which a fight started – nobody quite knew how. It was not even a struggle. There were only eight keepers, while from first to last forty or more ramblers took part in the scuffle.

“The keepers had sticks, while the ramblers fought mainly with their hands, though two keepers were disarmed and their sticks turned against them.”

One temporary gamekeeper, Mr E Beaver, was, according to the report, knocked unconscious and injured his ankle.

After the skirmish, the Manchester contingent continued up to Ashop Head, where they were met by 30 or so ramblers from Sheffield, who had taken the Jacob’s Ladder route to the summit from Hope. A celebration meeting was held (after stopping for tea) and: “The leader [presumably Benny Rothman] who at an earlier stage had asked us to trespass in spite of all danger now congratulated us on having trespassed so successfully.

“We were warned that some ramblers might be unfortunate enough to be fined, and for their future benefit, the hat was passed around.”

Their celebration over, the trespassers returned back down William Clough towards Hayfield. Near the water works, they were met by a contingent of policemen and one made to arrest one of their leaders, but he was chased off.

Their celebration over, the trespassers returned back down William Clough towards Hayfield. Near the water works, they were met by a contingent of policemen and one made to arrest one of their leaders, but he was chased off.

On the outskirts of the town, a police inspector suggested they form up into a column and they processed in, preceded by a police car and singing triumphantly.

Their happy mood soon turned to consternation, however, as gamekeepers went along the ranks of the trespassers and picked out the leaders, who were arrested.

The eyewitness report concludes: “As the church bells rang for Evensong, the jubilant villagers crowded every door and window to watch the police triumph.”

Of the six arrested, two were cotton piece workers, two were engineers, one a student and one unemployed. Benny Rothman and four others were jailed after a trial at Derby Assizes for between two and six months. After his term of imprisonment in Leicester, Rothman was jobless.

The arrests and imprisonment of the activists proved to be a turning point in public opinion. Ordinary members of the public were horrified at the sentence and even the establishment walking organisations supported the trespassers, albeit through clenched teeth.

The 1933-4 handbook of the Sheffield Clarion Ramblers, a Socialist walking organisation, quotes Frank Turton, honorary secretary of the Sheffield and District Ramblers’ Federation: “The mass trespass on Kinder, if it did nothing else, threw a little more illumination on the subject, and when Anderson, after being dismissed of the charge of grievous bodily harm, was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment for assault (which may mean anything worse than raising of the hand in a threatening attitude), the whole of the Federations of the country were aroused by what has been described as a savage sentence, and we are now exerting every effort to obtain full support for the [Access to Mountains and Rights of Way] Bill.

“It will be noted that there was no charge of trespass or damage preferred against any of the ramblers who took part in the Mass Trespass.”

“It will be noted that there was no charge of trespass or damage preferred against any of the ramblers who took part in the Mass Trespass.”

Present-day walkers enjoy Kinder Scout's summit, a pleasure denied to ramblers of the 1930s

A few weeks later, 10,000 ramblers gathered at Winnats Pass, between Castleton and Edale, for another mass trespass. It was the largest gathering of walkers in history. The right-to-roam movement, which had started in 1876 with the formation of the Hayfield and Kinder Scout Ancient Footpaths Association, was gathering momentum.

The Sheffield Clarion handbook declares sternly: “Every rambler is expected to be at the Access to Mountains Annual Demonstration in the Winnats Pass at 3.0pm”

That particular one was scheduled for Sunday, 25 June 1933. The leader, A Price, informs ramblers: “Route: Padley Chapel, Greenwood Farm, Hathersage Booth, Hathersage, Camp Green, Car Head Farm, Hook’s Car, Dennis Knoll, Gatehouse Farm, Hurst Clough and Saltergate Lane, Thornhill, Win Hill, Twitchill Farm, Hope, and riverside path to Castleton. Return to Grindleford as you please. 16 miles.”

Three years later, the Rambler’s Association, an amalgamation of the various rambling federations, was born, journalist Tom Stephenson touted the idea of a jubilee trail along the backbone of England, which would eventually become the Pennine Way, and a conference restated the idea of a Central Authority for National Parks.

But momentum in the right-to-roam campaign is a slow force. The Access to Mountains Bill failed to make it into the statute books until 1939 and even then it was in such a watered-down and counter-productive form that is was of no practical use to ramblers.

The Second World War intervened and it would be 17 years before the post-war Labour government passed the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act which led to the establishment of national parks as areas dedicated to enjoyment of the outdoors and to conservation. Importantly, the act also allowed for the setting up of access agreements with landowners.

In 1951, the Peak District National Park became, fittingly, the first to be set up and the following year the authority negotiated access agreements for Kinder Scout. Parts of Bleaklow were opened up soon after. The dream of Benny Rothman and his Manchester brigade of moorland battlers had become reality.

But of course, the story doesn’t end there. In fact, the story still hasn’t ended. It was not until 1965 that the Pennine Way officially opened and it was only with the Labour Government’s 2000 Countryside and Rights of Way Act that large areas of upland England and Wales were finally opened to the right to roam off public rights of way. Unsurprisingly, landowners and representatives of those controlling countryside gave dire warnings of the consequences and battled against the act’s passage through Parliament. None of the problems they predicted have come to pass.

But of course, the story doesn’t end there. In fact, the story still hasn’t ended. It was not until 1965 that the Pennine Way officially opened and it was only with the Labour Government’s 2000 Countryside and Rights of Way Act that large areas of upland England and Wales were finally opened to the right to roam off public rights of way. Unsurprisingly, landowners and representatives of those controlling countryside gave dire warnings of the consequences and battled against the act’s passage through Parliament. None of the problems they predicted have come to pass.

Kinder Scout is now access land under the Countryside and Rights of Way Act

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 gave walkers and mountaineers north of the border far greater freedoms, modelled on Scandinavian practice, with the right to wild camping, canoeing, and other outdoor activities across the whole of the nation’s wilderness areas.

And still the campaign continues. Coastal access has recently gained the thumbs-up, in principle at least, of the Environment Secretary David Miliband after a concerted campaign by outdoor groups and the newly-formed Natural England. Beyond that lies the hope that England and Wales may one day have the freedoms Scots hold to use their wild lands without the fetters that came with the Countryside and Rights of Way Act.

At the celebration of the Kinder trespass 70th anniversary, the 11th Duke of Devonshire made a public apology for his grandfather’s actions. He said: “I am aware that I represent the villain of the piece this afternoon.

“But over the last 70 years, times have changed and it gives me enormous pleasure to welcome walkers to my estate today.

“The trespass was a great shaming event on my family and the sentences handed down were appalling. But out of great evil can come great good. The trespass was the first event in the whole movement of access to the countryside and the creation of our national parks.”

The Ramblers’ Association, formed after the events of 1932, from the disparate walking federations that existed throughout the country, will be at this weekend’s celebrations in Derbyshire.

Kate Ashbrook, the association’s chairman, will tell the gathering at New Mills: “It is hard for us to imagine that a walk across a moor caused six young men to be jailed, but that is what happened to Benny Rothman and his comrades on these hills three quarters of a century ago.

Kate Ashbrook, the association’s chairman, will tell the gathering at New Mills: “It is hard for us to imagine that a walk across a moor caused six young men to be jailed, but that is what happened to Benny Rothman and his comrades on these hills three quarters of a century ago.

Rock outcrops on Kinder's edge

“They demonstrated for the right to roam; now we enjoy that right. Every time we go freely onto the moors and the mountains, or onto the local common, we should remember our debt to the mass trespassers.

“We now have two goals. The first is to see the right to roam extended fully to the downs of the midlands and the south of England. The second is to win freedom to walk around the coasts of England and Wales. On this we now have pledges from government. It will be our job to see those pledges are fully implemented.”

So next time you take that decision to veer off the footpath, and exercise your right to roam, just remember those young men and women who endured violence and jail so that our generation could stroll across the wilderness of Kinder’s plateau and all the other remote areas we can now enjoy without fear of the gamekeeper’s sticks and guns.

So next time you take that decision to veer off the footpath, and exercise your right to roam, just remember those young men and women who endured violence and jail so that our generation could stroll across the wilderness of Kinder’s plateau and all the other remote areas we can now enjoy without fear of the gamekeeper’s sticks and guns.

The groughs and hags of Kinder's interior wilderness

But don’t forget to take your map and compass and polish up your navigation skills. Even without the Duke of Devonshire’s henchmen, Kinder and Bleaklow can be dangerous places.

Jim Perrin

19 April 2007Congratulations on a judicious and exemplary piece - maybe we should all bear in mind (whilst feeling duly grateful, of course, for CRoW), what would have happened these days, in the aftermath of Thatcherite legislation unrepealed by New Labour, to Benny Rothman and his companions-in-protest. And maybe, too, we should keep due focus on the backward march that would ensue after an election victory for David Cameron and his Countryside Alliance cronies. One lesson Benny taught us - and exemplified throughout his long life - is that complacency in the face of powerful vested interest is invariably catastrophic to the interests of us the public, who alone are appreciative of the value of our fast-diminishing wild country. We should bear in mind continually that one of the first initiatives of the Thatcher administration post-May 3rd 1979 was the stuffing of all our environmental watchdogs with representatives entirely inimical to their proper operation. Benny spent the last twenty years of his life drawing atention to this, alongside his other social concerns. His warnings should endure...

Barry Levene

02 March 2012To coincide with the 80th Anniversary - Mass Trespass -Kinder Scout - April 2012.

MNVDISCS, are releasing a dvd plus an audio cd, of a filmed

interview with the late Benny Rothman, Tona Gillett is also

featured.

This filmed interview produced by Will Scally, has never been

broadcast.

If you require any further info` please do not hesitate in contacting me.

Regards,

Barry Levene.

Ted Scanlan

16 July 2018Hi there,

I work for Channel 5, on a program called Britain by Bike.

We would like to use a photo in our upcoming series - the one of Benny Rothman standing on a rock addressing the crowd. Do you happen to know the source of the photo/ who owns it?

Many thanks,

Ted Scanlan

Elephant House Studios - Channel 5

Bob

16 July 2018Hi Ted

I can't recall who actually supplied the picture to us, but the Kinder Scout events used to be organised by the Kinder & High Peak Advisory Committee. However, the Kinder Trespass website they used to run is no longer live.

You could try the Peak District National Park Authority. They may have contacts.

John Jones

13 February 2019Jim Perrin's ludicrous partisan prediction twelve years ago doesn't look too clever in retrospect, does it? It's straight out of the same socialist black-propaganda book as "the Tories will abolish the NHS", used to frighten people even though it's clearly an implausible claim and mysteriously never actually happens. After nearly a decade of another Tory government from 2010 we've not seen access to places like Kinder Scout stopped, and frankly nor was it ever likely that we would see "the backward march" on such issues that Perrin confidently forecast. After all, even the Duke of Devonshire in 2007, as the article points out (but Perrin, biased class warrior that he is, chooses to ignore), strongly supported the principle of access to open countryside.