Row after row of shiny new waterproofs, pristine fleeces and softshells; rucksacks with high-tech materials to shave the last few grams from the scales, boots to suit every type of terrain from frozen waterfall to blistering sand. The range of outdoor gear is mindbending.

Row after row of shiny new waterproofs, pristine fleeces and softshells; rucksacks with high-tech materials to shave the last few grams from the scales, boots to suit every type of terrain from frozen waterfall to blistering sand. The range of outdoor gear is mindbending.

Some of the prices are pretty astounding too, and it’s frightening to tot up the amount we sometimes carry on our backs when we struggle up the mountains and fells. We’re not talking pounds weight, but pounds sterling. Try the exercise yourself and be astonished at the worth of the average walker’s kit list.

So, clutching our platinum plastic or hard-won folding beer tokens, we venture into the Aladdin’s cave of the outdoor outfitter. It’s a fair bet we’ll have taken care to research and compare features, price, colour, size, length, weight, inside leg, outside edge… But how many of us look at the ethics behind what we slip on when we take to the wilds?

With carbon footprint in danger of supplanting our bootprint in the peat as the primary concern when buying outdoor equipment, grough decided it was time to peer between the hangers and shelves at the ethics of outdoor wear.

It has to be said that, for lovers of natural beauty and the great outdoors, climbers, walkers, hikers, rambler, paddlers, mountain bikers and all the other assorted –ers who take to our remoter areas are not always at the forefront of environmental responsibility. We can recall, not so long ago, a conversation with a shop owner – a keen winter climber – who declared he had given up on Scotland as a venue for ice climbing. Far more reliable and cheaper to get a Ryanair flight to Chamonix and get up close to some real ice action.

The irony of pumping out tons of carbon dioxide to reach the dwindling reserves of decent winter wilderness left because of climate change was, unfortunately, lost on our iceman.

The irony of pumping out tons of carbon dioxide to reach the dwindling reserves of decent winter wilderness left because of climate change was, unfortunately, lost on our iceman.

Right: Scottish Highland winter wilderness: Aonach Mor's cornices

We resist the building of windfarms in our wildernesses yet can’t resist the temptation to jump in our two-litre turbocharged machines and travel 400 miles to reach said wilderness and catch the atmosphere before the last mountain hare disappears or the fragile tundra is turned to soggy, warm bog.

And we have to admit, we at grough are just as guilty as the next boot-clad wilderness walker.

So, ethics: can we walk with an easy conscience, or must we shoulder the additional burden of guilt along with the kilos of gear in our rucksack. grough’s thoughts on ethics were prompted by the claims of a new company in the circus of gear producers. El Alto labels its range ‘socially responsible outdoor clothing’. Here’s what its website says: “Sweat shop is such a well known term now and sadly where much of the clothing on Britain’s shelves comes from. As long as there is a demand for rock bottom price clothing, there will always be someone who will choose to meet that demand.

“We aim to show that it doesn’t need to be like that, that people can make a choice which is an ethical one but at the same time doesn’t break the bank or compromise on quality.”

The El Alto range is small at the moment, consisting mainly of fleeces and vests, plus an odd hat and snood. To be honest, its prices don’t seem that much higher than many of the well known brands. So how is it different?

Its clothing is made in Bolivia. It says its products are ethically sourced, staff fairly treated and a fair price paid. Should we be adding El Alto range to our shopping list along with fair trade coffee, chocolate and bananas? El Alto says its workers are paid almost double a typical wage, four times the national minimum wage. While it admits its rates are low by western standards, it goes some way to improving the livelihoods of its workers.

In addition, it says its production staff work reasonable hours in comfortable surroundings.

El Alto says one percent of all its sales goes to Bolivian social and environmental projects and a further one percent is donated to the project One Percent for the Planet.

Paramo, which was started by Nikwax founder Nick Brown but which is now a separate company, also produces much of its clothing in South America. It established a factory in Bogota, Colombia, working with the Miquelina Foundation, the brainchild of a Colombian nun, Esther Castano Mejia, who belonged to an order working to rescue women from prostitution. The order bought a few second-hand sewing machines and the foundation was born.

Now, it works with Paramo and has gained the ISO 9001 standard and an award presented by the country’s president for its contribution to the community.

South America is rare as a country of origin for outdoor gear. European manufacturers are almost as rare and British ones sparser still. Tog 24, Snugpak, Keela, Buffalo, Rab and Walsh, manufacturer of fellrunning shoes, are among the British companies still producing some of their products in this country. Specialist clothing manufacturer Slioch makes made-to-measure waterproofs at its Poolewe factory.

South America is rare as a country of origin for outdoor gear. European manufacturers are almost as rare and British ones sparser still. Tog 24, Snugpak, Keela, Buffalo, Rab and Walsh, manufacturer of fellrunning shoes, are among the British companies still producing some of their products in this country. Specialist clothing manufacturer Slioch makes made-to-measure waterproofs at its Poolewe factory.

Left: this Scarpa boot is made in Italy

Some boots are still made in Europe by established companies such as Scarpa, Kayland, Meindl and Raichle. However, a European house name is no guarantee that a product has come from our continent.

Arc’teryx makes most of its products in Canada, and its prices probably reflect the high labour costs there.

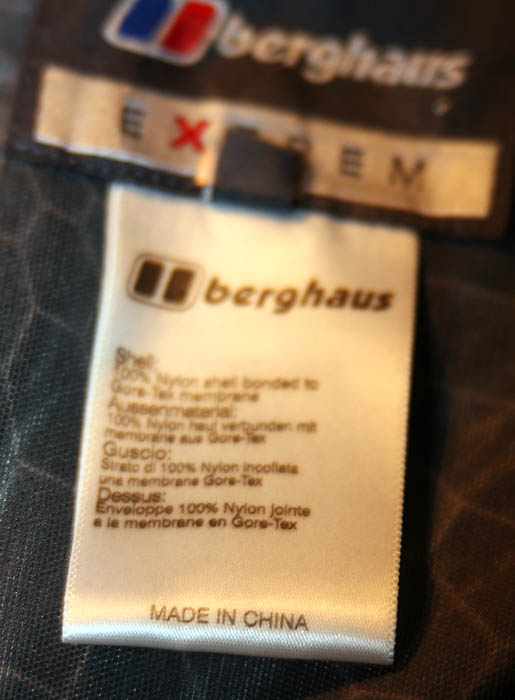

In an outdoor magazine’s latest gear guide, of 154 waterproofs tested, 102 were manufactured in China. Brands sourcing their jackets in the People’s Republic include Berghaus, Columbia, Gelert, Golite, Karrimor, Marmot, Montane, Mountain Hardwear, Patagonia, Rab, Sprayway and The North Face.

China is the new powerhouse when it comes to outdoor clothing. More than half the soft-shells and two-thirds of the sleeping bags included in the test were China-made. Even production of walking boots is moving from Europe to the Far East, with Italy eclipsed by the oriental Communist state.

China is the new powerhouse when it comes to outdoor clothing. More than half the soft-shells and two-thirds of the sleeping bags included in the test were China-made. Even production of walking boots is moving from Europe to the Far East, with Italy eclipsed by the oriental Communist state.

grough spoke to Ruth Rosselson of Ethical Consumer magazine, which recently looked at some types of outdoor clothing companies. She said: “We have done something on fleeces and walking boots.

“The outdoor clothing industry is really no different to the clothing industry in general and will have the same problems.

“Wages paid in China are not enough to live off, and if you look at Bangladesh, here too, the legal minimum wage is not enough to live off. This leads to people working in excess of 60 hours.

Above: a Berghaus waterproof, made in China

“Very few companies are doing enough to make sure that workers are treated properly.”

One of the big players in the British clothing market has an answer to such complaints. Finchley-based Pentland Group PLC, which took over the Berghaus brand in 1993 and has a 75% holding in the Brasher Boot company, has a group code of employment standards for suppliers. Its code says: “Working hours comply with national laws or benchmark industry standards, whichever afford greater protection. Workers are not, in any event, required to work more than 48 hours per week on a regular basis.

“Workers are allowed at least one day off on average per week.”

On pay, Pentland’s code says: “The wages and benefits paid for a standard working week are at or above national minimum legal levels or industry benchmark levels, whichever are higher. In any event, wages are always sufficient to meet basic needs and to provide some discretionary income.”

Below: A rucksack from The North Face

One company that consistently comes out well in ethics reports is Patagonia. The company, founded in 1973 by Yvon Chouinard, has a range of policies that mark it out from some others. For instance, Patagonia wants you to send them your underwear. Please wash it first, though: recycling polyester base layers has less environmental impact than creating the fibre from raw material. It has also used recycled PET drinks bottles to make fibres for its clothing. More than 86 million bottles have been used so far. Any cotton used in its ranges is organic.

One company that consistently comes out well in ethics reports is Patagonia. The company, founded in 1973 by Yvon Chouinard, has a range of policies that mark it out from some others. For instance, Patagonia wants you to send them your underwear. Please wash it first, though: recycling polyester base layers has less environmental impact than creating the fibre from raw material. It has also used recycled PET drinks bottles to make fibres for its clothing. More than 86 million bottles have been used so far. Any cotton used in its ranges is organic.

Patagonia also donates 1% of sales to the restoration and preservation of the environment and allows employees two months paid time off to work for the environmental group of their choice.

When Ethical Consumer carried its report on fleeces, it was no surprise that the Ventura-based company came out tops. It’s also the only company grough has so far found that has a quotation from French author and aviator Antoine de Sainte Exupéry as one of its inspirations.

Ruth Rosselson of Ethical Consumer magazine again: “Our best buys for fleeces were Patagonia, Mountain Equipment, Polaris and Rab. They were best in terms of corporate performance. Rohan also offers a repair facility for its fleeces, which means less use of resources.”

She also says companies need to open up their policies to scrutiny. She said: “Transparency [in companies’ sourcing] is important.

“When we did the report, Patagonia was the only one with an independently monitored code of conduct. Pentland may have one by now. They are quite good with disclosure of information.”

Oxfam says average income in China is only one twenty-fifth of that in France and, despite the country’s massive economic growth in the past 20 years, more than 100 million of its inhabitants live in absolute poverty.

Last autumn, there were riots in Bangladesh as garment workers took to the streets to protest at low wages and poor working conditions. A Government body recommended the first rise in the minimum wage for 12 years. The proposal was to raise the minimum to £13.27 a month, including house rent and other allowances. Bangladeshi trade unions had called for nearly three times that amount to be set as a minimum.

Labour Behind the Label (LBL), a campaign group trying to raise awareness of conditions in the garment industry in developing countries, says: “Many [companies] use a formulation along the lines of that in the Ethical Trading Initiative base code: ‘national legal standards, whichever is higher. In any event, wages should always be enough to meet basic needs and to provide some discretionary income.’ The difficulty with this statement is that neither national legal standards nor industry benchmark standards come close to meeting basic needs.”

Labour Behind the Label (LBL), a campaign group trying to raise awareness of conditions in the garment industry in developing countries, says: “Many [companies] use a formulation along the lines of that in the Ethical Trading Initiative base code: ‘national legal standards, whichever is higher. In any event, wages should always be enough to meet basic needs and to provide some discretionary income.’ The difficulty with this statement is that neither national legal standards nor industry benchmark standards come close to meeting basic needs.”

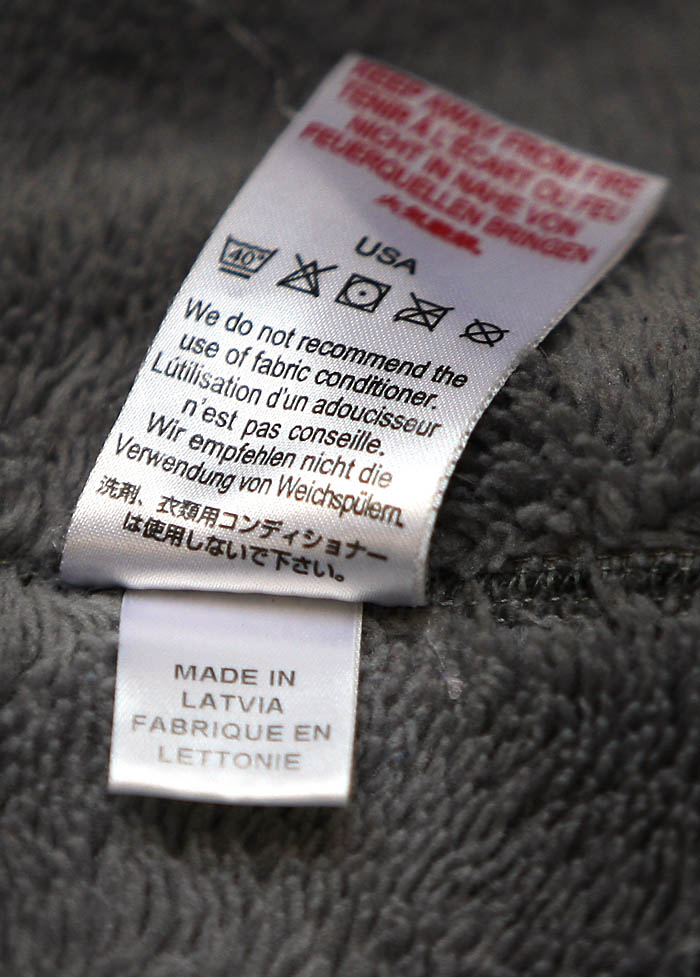

Right: behind the label: how many of us look to see where our clothing is made?

At least we now know the source of the Pentland policy. The organisation also says that many workers in the Far East garment industry are denied union rights.

LBL asked a large number of retailers and producers at the beginning of last year what progress they were making towards ensuring fair pay for clothing workers. Most of the companies were retailers and the only outdoor gear manufacturer questioned was Pentland again, which was viewed as middling in its response, having taken some steps to address working conditions, but being more interested in ticking boxes. TK Maxx, which often has discounted outdoor clothing on its rails, fared slightly higher with a ‘could do better’ rating. Only Gap and Next, neither of which are players in the outdoor industry, were ahead of the field.

Welsh firm howies, which has a strong environmental policy and allows staff days off when it’s too nice to work, has just been bought out by giants Timberland. howies makes biking and skateboarding wear.

So, you pays your money; you takes your pick. How important a firm’s ethical stance is may or may not influence your choice of clothing and gear in the future. Or maybe it will still be down to the quality of zips and the shade of lime green. grough can’t help thinking, though, that outdoor clothing and equipment manufacturers are going to come under more and more pressure to come clean environmentally and in terms of human rights if they are to keep their market share.

Now, where’s that El Alto catalogue?

Links

Pentland Brand PLC (owners of Berghaus)

R J Anderson

12 October 2008Your article states: "Patagonia ... allows employees two months paid time off to work for the environmental group of their choice." How often? Each year, every two years, there working lifetime? This sloppy writing really irritates me. A little more care would be appreciated.

I also feel quoting so liberally from a magazine like Ethical Consumer is rather less than rigorous. Better to do your own research than piggy-back on people who may have special interests or only see the world from their particular point of view. Their view and opinions of China seem particularly lacking in knowledge.

And while I'm at it, what's wrong with the initial capital in a proper name. Would Grough be such a problem? It certainly would make it easier for readers.

pete little

23 May 2010Quite right, it is so much easier to read Grough than grough.

I was struck by your point about gear. For my part, I have only ever worm Walshes & an old vest & shorts in summer & in winter a pair of koflachs bought in 1979, grivels someone lent me & then didn't want back and various old odds and ends. I admit to having a pair of very painful old Fires. I must replace my ropes & gear sometime.

Sorry, Koflachs & Grivels

People buy so much absurd gear. It doesn't have much to do with climbing so far as I can tell. & why do they all have little beards and drop tissues all over the place. & they make such a fuss about a few miles. Last week I ran up Glen Nevis to the grey corries, back over aonachs, sgurr dearg & the ben & a pint in the clachaig, then met a chap who fancied doing the gully in the dark, down by 3.45am - average day