A pair of hill sleuths who set up G&J Surveys, which made a hobby of measuring the heights of hills and mountains, are celebrating the outfit’s tenth birthday.

John Barnard and Graham Jackson marked the anniversary in the only way possible: setting out to settle the score on three hills in northern England, to decide whether they qualified as nuttalls.

Here, they recount the origins of their mission to measure the heights of some of Britain’s peaks, and the latest results of their anniversary survey.

We know what you’re thinking. “Why on earth would anyone want to measure the height of a mountain, when Ordnance Survey produces the best maps in the world and it has all been done for you?” Why indeed? But hold on, was the idea so silly? How did all this get started?

The Database of British and Irish Hills (DoBIH) also celebrates its 15th birthday this year. This was founded by Graham Jackson and Chris Crocker, initially as a personal tool to help them log their own hill ascents. However, over the years DoBIH has evolved into something much bigger with currently six editors and many hillwalkers who supply data to it.

An important step in its evolution was related to the availability of hand-held GPS units. Using a six-figure grid reference to pinpoint a position means that the actual position can be up to 140m distant. However, this uncertainty falls to 1.4m with a 10-figure grid reference.

Now modern hand-held GPS units are not capable of giving a grid reference to within one metre but certainly 5m is possible. With DoBIH logging 10-figure grid references for the summits of hills, it soon became apparent that summit positions are not always so clearly known to warrant this level of accuracy. Hence the obvious conclusion that summits needed to be identified with a survey technique to justify the GPS measurement brought G&J Surveys into existence.

John Barnard and Graham Jackson are interviewed on Tan Hill by Julia Bradbury for Countryfile. Photo: G&J Surveys

Back to Ordnance Survey maps. The heights of features on maps do change with map edition. For example Beinn Teallach, the mountain in Scotland just north of Glen Spean, used to belong to the list of corbetts with a map height of 913m. When a new series of maps was produced its height was given as 915m and it became a munro. In order to fulfil its remit of mapping every area in the country at least once in five years, a mammoth task, Ordnance Survey uses a technique called photogrammetry in which an aeroplane is used to take aerial photographs of the landscape.

From these photographs Ordnance Survey produces its maps. Photogrammetry measures heights to an accuracy of +/-3m giving maps that are superbly fit for purpose – you won’t get lost using one – but nevertheless the technique can result in corbetts suddenly becoming munros.

With the increasing popularity of hill-bagging, the accuracy of hill lists was becoming more important.

So the idea of G&J Surveys also measuring the height of hills as well as identifying summit positions was born and our first purchase of equipment was a surveyor’s level and staff from our local supplier M&P Surveys in Ellesmere Port.

Armed with this shiny new equipment and lots of enthusiasm we set off for Birks Fell, a 609m hill in the Yorkshire Dales that had failed to make it on to the latest list of 2,000ft mountains in England and Wales compiled by John and Anne Nuttall and published by Cicerone in two volumes – a hill of 2000ft or over in England and Wales is considered to be a mountain.

Old maps had given the height as 2,000ft (610m) and Birks Fell had therefore appeared in the earlier lists of Bridge and Buxton & Lewis. There were two trig pillars on the long ridge of the hill and the plan was to find the summit position, for which there had been much speculation within the hillwalking community, and then determine its height relative to the trig pillars.

The flush brackets on trig pillars are generally known to an accuracy of 1ft. After two successive surveys, on one of which we were accompanied by our wives, we determined the height of Birks Fell to be 2,002.6ft (610.4m). John and Anne submitted our result to Ordnance Survey and further research by OS confirmed our result. We had found a new mountain and G&J Surveys was in business!

For the next 18 months, we continued with the level and staff, measuring drop – the height difference between col and summit – for many hills. Drop is an important criterion for several hill lists.

Cadair Bronwen North East Top was removed from the list of Nuttalls for failing to achieve the 15m of drop necessary for that list; we measured it to be only 10.7m. But during this time there was increasing frustration that we had no way of measuring height directly, only with respect to trig points.

This led one of us, John Barnard, to research the options and the idea of using Global Navigation Satellite System technology was born. Following discussions with Leica Geosystems the plan was hatched to measure the heights, using a Leica 1200 GPS receiver, of two mountains in Wales both just below 2,000ft, Craig Fach (609m), a small prominence on the ridge from Pen-y-Pass to Crib Goch and Mynydd Graig Goch (609m), a hill at the south end of the Nantlle Ridge.

This instrument is a survey-grade GPS receiver and we were told it was capable of measuring height to 5cm or better. To prove the point James Whitworth from Leica Geosystems would accompany us on the survey and ensure that the 1200 was put through its paces. While Craig Fach remained below the magic height, Mynydd Graig Goch made it with just six inches to spare. This happened in 2008, at the time of the financial crash, when everything in the world seemed to be going down and doom and gloom was in every news feature.

Here, however, was something that had actually gone up and it caught the imagination of the media. We were summoned to a field at the base of the mountain where the world media had assembled. There were vans, masts and aerials everywhere, a most intimidating sight. For our very first live radio appearance the interviewer said, “Ten seconds to go and remember you will be speaking to six million people.” No pressure then! In fact the story not only featured on the main BBC television news and in all the major newspapers, it also featured in news items as far apart as Patagonia and Istanbul. So, GPS technology had worked and James Whitworth had a sale and we had a survey-grade GPS receiver.

From those heady days we have made many measurements and re-classified many hills and mountains. Just three months ago a mountain in Scotland, Cnoc Coinnich, was re-classified from a Graham to a Corbett as a result of our work. These measurements have been ratified by Ordnance Survey, and Mark Greaves, the OS geodesist, has been a great help to us and advised over best surveying practice.

So, we wished to celebrate the tenth anniversary of G&J Surveys and 15th birthday of DoBIH. The plan was hatched to have a joint celebration and what better way to do it than with a survey?

Chris Crocker and Jim Bloomer had reported to us that Tinside Rigg in the Pennines, which is over 2,000ft high, might have sufficient drop from its summit to its col to be classified as a nuttall. We also were aware that its near neighbour Long Fell was a candidate too.

Three editors of DoBIH, Simon Edwardes, Jim Bloomer and Chris Crocker, were keen to join in. We had also contacted John and Anne Nuttall and they supported the idea and were keen to join us. So it came to pass that the ‘Magnificent Seven’ met up in the comfortable independent hostel of Kirkby Stephen ready for action.

As we were in the vicinity, John and Anne suggested we might also like to accompany them on a revisit of Bram Rigg Top in the Howgills during the two days of our meet. This nuttall had been surveyed a few months previously by Myrddyn Phillips, and he had informed John and Anne that his results showed the drop to be less than 15m so the hill should be considered for demotion.

The following morning dawned grey and overcast, but at least it was dry. John Barnard takes up the story. “To be successful we required visibility at higher altitudes in order to be able to use the level and staff to locate the exact summit and col positions. The cloud was hanging around the tops and it didn’t look promising early on. However, as we drove to the start of the walk at the hamlet of Hilton, breaks in the cloud began to appear and our spirits rose. Game on!

Graham Jackson said: “Our numbers were swelled with the arrival of two more colleagues, David and Ed Gradwell, and soon we were kitted up and the gear distributed among the team and off we set. We followed a good track, marked with posts on its upper reaches, and after an hour and a half we were on the top of Tinside Rigg with only a light breeze and broken cloud above us.

“Conditions for surveying were near perfect.”

John Barnard said: “We collected GNSS data on Tinside Rigg and then split our forces. Chris, Simon and I started line surveying the two potential cols for Long Fell, while Graham and Jim collected data on the col of Tinside Rigg.

“An hour-and-a-quarter later Graham and Jim appeared. By this time we had determined the true col position of Long Fell, so Graham and Jim then collected GNSS data there while Chris, Simon and I line surveyed to the summit of Long Fell. Finally, Graham and Jim completed their task at the col and arrived at the summit to finish the survey by collecting GNSS data on Long Fell.

“Voila! The survey was completed with time to spare before darkness approached. We celebrated with slices of Tinside Rigg cake kindly baked and carried by Anne. We decided she should come surveying more often.”

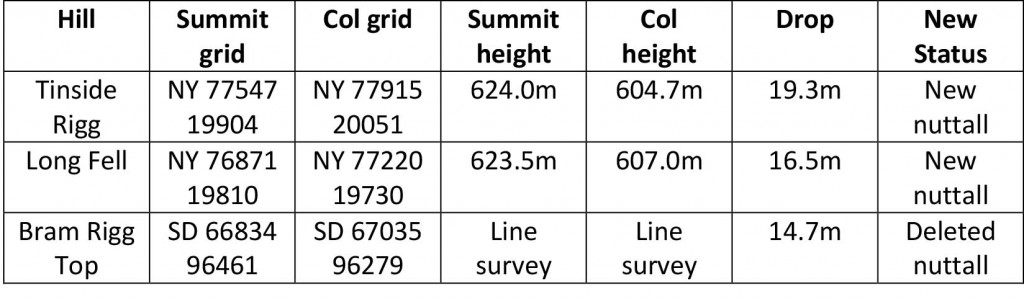

The next day we walked with John and Anne to the summit of Bram Rigg Top and completed a line survey there in order to measure its drop for ourselves and confirm the previous survey. This rounded off two days of surveying, but what of the results? These are shown below.

It’s not every day that three changes are made to such an established and well researched list as the Nuttalls. What a way to celebrate an anniversary.

Footnote: For those wishing to climb Tinside Rigg and Long Fell it should be emphasised that they lie on the Warcop military range and the Ministry of Defence restricts access to only a few days a year. Access days should be checked via MoD at Warcop. On any other day red flags fly at access points and entry to the range is then strictly forbidden for obvious reasons. Tinside Rigg lies close to the footpath that crosses the Warcop Range from Hilton to connect with the B6276 at NY825195.