What goes through a fellwalker’s mind as he or she slogs up a Lakeland mountain?

Often it’s concentration on route finding; a brief stop to admire the view; or just the sheer effort of ticking off a few more contour lines on the relentless climb to the summit.

How many of us stop to wonder how these glorious fells actually came to be here in the first place?

One man does. Peter Wilson is a keen hillwalker, runner and cyclist. He likes to go ski touring too though he admits he doesn’t do all simultaneously. The Lancashire-born outdoor enthusiast also happens to be a Reader in Quaternary Science at the University of Ulster and his quest is to make your trips into the hills more informed and more enjoyable.

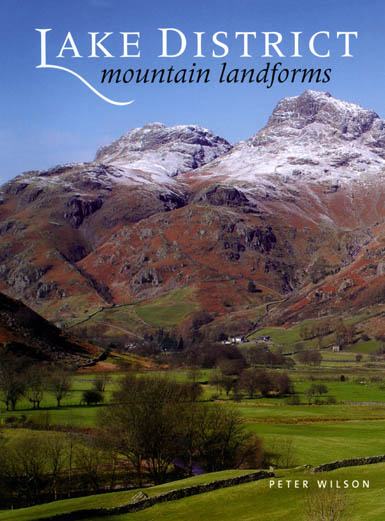

Wilson’s new book Lake District Mountain Landforms is a glossy, illustrated encyclopaedic explanation of the origin of the Lakeland fells, valleys, lakes and other landform features we probably take for granted as our boots traverse the rocks, bogs and meadows of the Lake District.

Aimed firmly at the fellwalker and outdoor enthusiast, Wilson’s book goes way beyond the usual ‘the Lake District is the product of glaciation’ tome to detail just how the landscape came to be the way it is and how it is still changing.

How many casual visitors and walkers realise, for instance, that the central fells of the Lake District – the Scafell range, Gable and Pillar, the Coniston fells, Helvellyn and High Street – would once have been a seething cauldron of lava? All of these magnificent mountains are the result of volcanic activity more than 400 million years ago.

These Borrowdale Volcanic mountains form one of the three main geological types in the Lake District, the others being the Skiddaw group – sedimentary rocks and the oldest in the area – and another group of slightly more recent deposits of mudstone, siltstone, sandstone, gritstone and limestone know as the Windermere Supergroup, in parts 8km deep.

The Howgills, beyond the Lake District national park, also belong to this ‘supergroup’.

Tectonic activity and uplift followed, with much of the uplands of the area being formed during this period.

Throughout Wilson’s book there are plenty of examples, with photographs, of the various rock types and formations and anyone familiar with the Lakeland fells will instantly recognise the explanations of their distinct shapes.

The author then leads on to the periods of glaciations – very recent in geological terms, up to only 12,000 years ago. He explains why, for instance, Helvellyn and its neighbours have such exciting eastern aspects and tamer western slopes.

There were certainly at least three major periods of glaciation, though there could have been many more. Some would have seen the whole area covered in deep ice, while others would have affected only the mountain tops. A recent picture of Baffin Island gives a clue as to how the Lake District might once have looked.

The features after which the area is named – its lakes – are also a product of glacial activity, carving out deep cavities. Three lakes have bottoms which are below sea level.

And the thrill-seekers on Striding Edge, Swirral Edge and Sharp Edge have been well served by the glacial period, their arêtes the product of glacial action, as are the cirques – combs, corries and all the other names by which they are known – for instance the bowl containing Red Tarn on Helvellyn.

The upland area is still subject to a similar climate, though without the huge iceflows. Screes, for example, are common and are the result of the freeze cycle that still occurs. The uplands may often be frozen, but the change to their forms is not, and the changes continue now.

Frost heave can wreak havoc with felltop paths just as much as the constant battering from boots, and earth tremors can still cause major events on the fells. Borrowdale’s Bowder Stone, one of the biggest boulders in the whole area, is the result of a rockfall. You certainly wouldn’t have wanted to be in the way of this huge rock as it thundered down the hillside.

And if you want to know where the Lake District’s only known rock avalanche took place, the book will tell you.

The major floods such as that in 2009 can also have profound effects on the landscape. Places only a short distance apart can have huge variations in rainfall, with a major influence on how the landform changes.

Water can also move sediment and rock around, both over short periods and in the longer term. It is thought that Bassenthwaite Lake and Derwent Water were once one large lake until river deltas formed enough solid land to separate them.

And, of course, the mountain tarns, from the Old Norse tjorn, are another major area of interest for those with an eye for landform. Up to 730 have been counted, with about half on the Borrowdale volcanic group and only 10 per cent on the Skiddaw group.

Most walkers wouldn’t associate the Lake District with limestone, but there are two expanses on the fringes of the area, and these provide some of the best technical language with which the amateur geomorphologist can bamboozle fellow walkers.

Try to explain the difference between flachkarren and kluftkarren and then you can move on to kamenitzas! Or if it all gets a bit Germanic for you return to the valleys for a view of the roches moutonnées.

There is certainly quite a bit of complicated terminology, but if you get stuck, there is an index and Wilson helpfully throws in a little self-test chapter at the end in which you can revise your new-found knowledge of Lakeland geomorphology, along with a diagram into which are packed many of the main features.

This is a book that will reward re-reading, as there is such a wealth of information to take in. It will certainly enhance any hillwalker’s trips into the mountains of Cumbria.

Lake District Mountain Landforms is published by Scotforth Books and is available priced £20.00 and can be ordered from all good bookshops. Hardback 212 pages. ISBN 13: 978-1-904244-56-1

Alternatively, click on the following sponsored link to open up a PDF to print out and order by post for £20.00 plus £2.95 postage.